The pain of not knowing

Constant access to always-helpful AI robs kids of the struggle that leads to learning

I had a recent conversation with Robert Gulotty, a professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago. I asked him how his teaching had changed with the rise of AI. He said it has been a huge disruption that has transformed how he teaches.

But not in a good way. Yes, he said that it’s nice that it’s sometimes easier to make lecture notes or presentations. But the real problem is that students use the LLMs to do the work for them, and miss out on the productive struggle that leads to real learning.

There’s been just an enormous change away from a standard of education which involves a lot of writing and thinking by yourself and turning it in outside the classroom. That is decreasing and it’s being replaced by oral presentations and in-person exams.

The evaluation and the homework - they force the students to engage with the material. And if you don’t do the work, it’s really hard to learn. The pain is sort of a memory and learning device. The fact that you have to work through all the problems and all that suffering helps you remember and learn things.

When I was in college, I spent many late nights wrestling with assembling sources, writing papers, and doing really annoying and difficult problem sets. The struggle is what builds the mental muscles, what helps you be stronger. I sat through plenty of lectures where I was lost, and didn’t understand what was going on. And in the pre-AI pre-smartphone era, I had no choice but to just sit and try to figure it out.

But for many students today, they have easy access to a friendly, always on companion who can help interpret everything. Dr. Gulotty shared that some of his students rely on AI during his lectures:

I’ve had students who just sit there in class and type everything I say into ChatGPT to help them understand it, sentence by sentence. And they go to the textbook and rather than thinking about what the words say, they’ll just type it into ChatGPT and say, “Explain this to me.”

And they do that sentence by sentence, equation by equation. Part of equation by part of equation. So they never experience the pain of not knowing.

This is a big problem. Who among us can resist the pull of an easy, always on, anonymous and free tool that just makes everything easy?

Ubiquitous AI is hard to avoid, even if you want to

This week there was a deep report released by the Brookings Institution on the risks and promise of AI in education (full report). The researchers surveyed a few hundred people around the world and analyzed many of the studies therein.

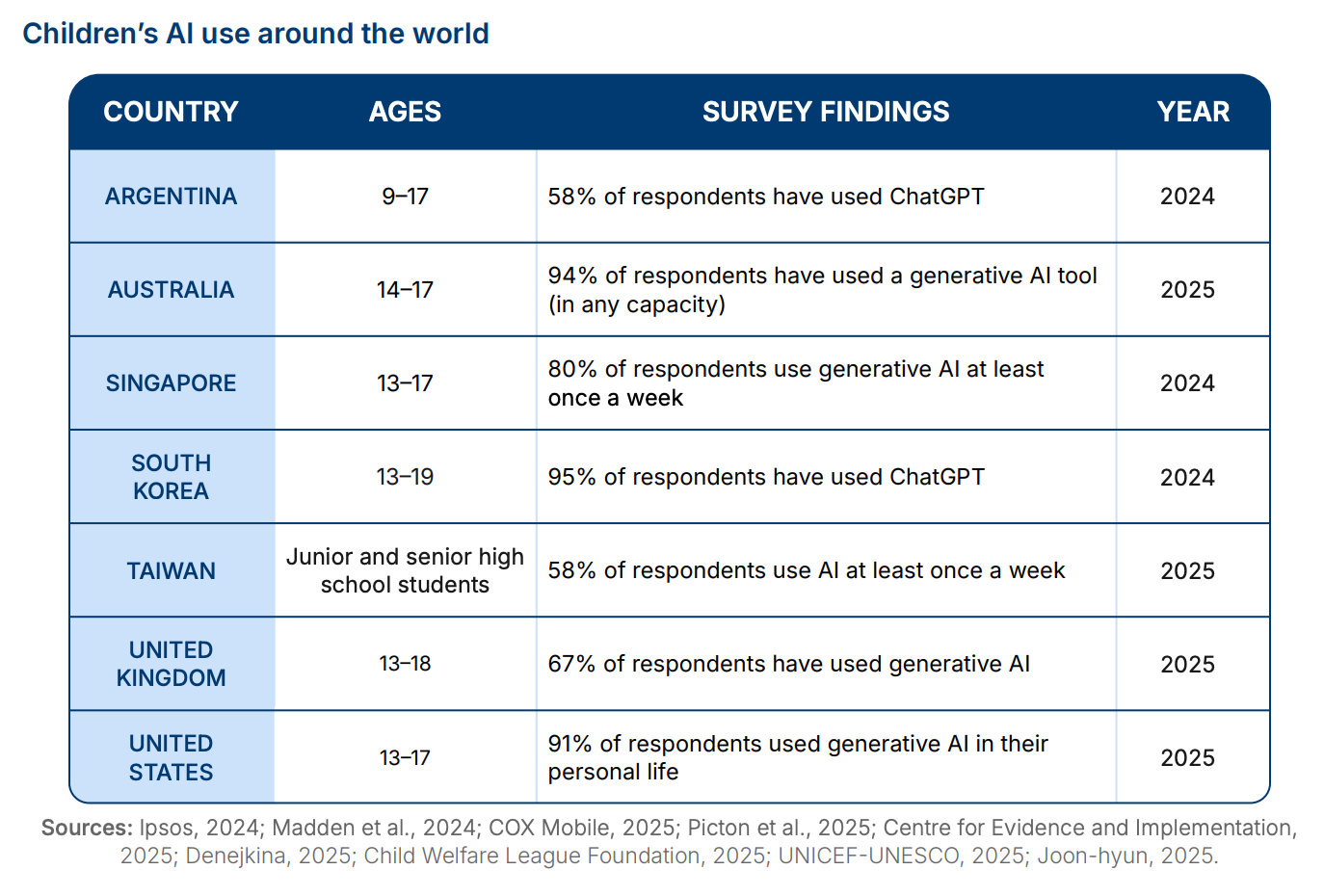

The first key takeaway: student use of AI is ubiquitous and worldwide. The vast majority of children surveyed in many countries have used AI. In the United States, more than 91% of children age 13-17 have used generative AI in their personal life, according to a survey from May 2025. Other studies have shown similar depth of usage.

And teens use AI in lots of contexts, in school, at home, and elsewhere, which means neither districts nor parents really have control over the whole picture:

The lines between education technology, friendship, information query, and entertainment are blurring. Students in our study report using AI through general purpose LLMs, social media, Internet search, video games, and education technology, often moving fluidly between these platforms …

Given their pervasive presence in everyday applications, students find it challenging to avoid using AI altogether.

So it kind of doesn’t matter what AI is used within the classroom context. Students (and adults) have nearly universal access, at home and at school. But if students have easy access to something, then it is more likely they’ll be tempted to use it.

One high school student shared with me that his district has adopted the free Gemini education suite for this school year. Since then, he says students are “cheating like crazy” and just using it for everything. This should not be a surprise - when things are easy and available, then people use them more often.

Students are often required to use Google Docs for assignments - but they have recently embedded a “Help me write” feature directly in the app. Sure, students could go out to ChatGPT - but now the AI is just easily embedded right there!

We know that when junk food is present in schools, kids eat more of it - even if they know they shouldn’t. So why wouldn’t the same apply to AI? Who can resist the temptation?

AI is uniquely problematic for kids

“AI does not accelerate children’s cognitive development—it diminishes it.”

The Brookings report highlights several risks and benefits to AI - but the one risk that really worries me is the increasing evidence that access to AI can stunt students’ cognitive development. Even if AI tools do help students improve learning in certain areas, the broader problem is that they just make life too easy.

The overuse, and even the routine use, of AI is fundamentally and negatively reshaping how students approach learning; this has profound implications for cognitive engagement, the development of practical skills, and existential questions about human purpose and agency. Study participants identified this threat to student learning as the greatest risk posed by AI.

The issue is fairly simple: constant access to an AI fosters dependence. Learning happens when you try hard problems, and then work through the solutions. But students find success using chatbots, then they grow to depend on them - and don’t develop the underlying critical thinking and literacy skills to fall back on when AI hallucinates, shows bias, or is just not available.

AI represents incredibly powerful technology, and professionals doing real work get enormous value from it. But they have years of experience to fall back on. But if the goal is learning, then having an AI do the work can get in the way. Eric Wastl, writer of the incredibly fun annual Advent of Code contest, points out “If you send a friend to the gym on your behalf, would you expect to get stronger?”

The Brookings report goes into a great summary of the issue:

The people harnessing these powerful AI tools are professional adults with fully matured brains. They have already developed sophisticated metacognitive and critical thinking skills that undergird their approach to their work. They have deep expertise in their domains, and the cognitive flexibility that comes with such expertise, allowing them to navigate, evaluate, assimilate, reject, and strategically use the information AI generates.

For students, the situation is fundamentally reversed. They are not mini-professionals. Their brains are developing, undergoing crucial processes of neural pruning and strengthening that depend on repeated cognitive effort and struggle. They lack the metacognitive skills, critical thinking abilities, and neurobiological maturity of adults. School exists precisely to build these capacities through sustained engagement with challenging material.

The productive power of AI tools, which amplifies adult expertise, can undermine this developmental goal when placed in the hands of learners. Cognitive development requires the effortful processing, mistake-making, and problemsolving that AI too easily circumvents and that many students are willing to bypass. Used liberally, AI is not a cognitive partner; it is a cognitive surrogate. It does not accelerate children’s cognitive development—it diminishes it.

Offloading diminishes capacity

The report cites several studies that provide evidence of reduced abilities in people who have access to digital tools like phones, search engines, and AI.

“Teachers report a digitally induced “amnesia” (Lee et al. 2025) where students cannot recall information they submitted or commit that information to memory, resulting in a loss of basic factual knowledge of a topic or domain.” Lee et al, The Impact of Generative AI on Critical Thinking.

“The ease of offloading work to AI is negatively impacting students’ love of learning, curiosity, self-confidence, sense of self-efficacy, sense of agency, and capacity for ethical reflection and nuanced problem solving” citing Bozkurt, et al, The Manifesto for Teaching and Learning in a Time of Generative AI.

Critical thinking is particularly at risk. One paper in particular was published last year by Michael Gerlich in Switzerland. It shows just how dangerous the lure of AI can be to our critical thinking skills.

Gerlich points out:

Because humans have evolved to cognitively offload, students naturally take shortcuts when given the opportunity. As cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham observes in his essay, Why Don’t Students Like School? “Unless the cognitive conditions are right, we will avoid thinking.” For teachers we interviewed, they see Willingham’s observation confirmed in their classrooms as students become consumers, not producers, of information.

As AI tools continuously improve, they become increasingly seductive to use, creating what amounts to an existential danger to learning itself

When chatbots do the work

When students do the work, they learn not just the immediate goal of the assignment, but the broader mechanism of how to think. One professor at University of Chicago, Russell P. Johnson, described the essential problem of what happens if students rely on AI to do their writing:

I’ll encourage you to think about what will happen if you use AI and don’t get caught. What will you miss out on if you subvert the writing process? Is learning how to write argumentative papers simply a drudgery to be automated away as soon as possible, or is it a spiritual exercise?

When I assign you to write a four-page paper on the Zhuangzi, for instance, it is not because I am under the illusion that you will need that knowledge later in your professional life. Writing a four-page paper on the Zhuangzi will not prepare you to compete in the high-pressure economic landscape of twenty-first-century America.

No, the reason why I insist you do writing assignments like this is that they give you valuable practice discovering insights and communicating them to others. Reading texts closely, encountering a problem, developing a plausible interpretation, and persuading readers of that interpretation—these are the steps one must go through in order to write a good paper. Going through these steps again and again makes us clearer thinkers and better communicators.

That essay was written in April 2023, just a few months after ChatGPT launched. Since then, his predictions have come to pass - and we are only at the beginning of the age of AI in schools.

The future is unclear

Teachers are facing a challenge: what to do about this cognitive offloading? The report has a few recommendations, but at the core we need to shift educational experiences in school. AI is here, and only getting more powerful by the day - we cannot only return to the “old school” methods of teaching. Instead, they suggest schools adopt child-friendly product design - AI tools that challenge and help students learn rather than doing the work for them. But cell phone bans and blue book exams will only get us so far.

The authors leave us with the acknowledgement that we don’t really know what exactly needs to be done: “None of us have all the answers right now. And yet the stakes to get AI right for our children could not be higher.”

In future posts, I’ll go deeper into examples of what educational experiences are working and how we can maintain rigorous education when students are surrounded by ubiquitous tools that can easily do the work for them.

I really appreciate the academic rigor brought to this discussion. This debate feels like an evolution of the "screen time" era. Just like screens aren't just good or bad for kids, the same is true for AI use where the how matters a lot.

In the popular MIT "Your Brain on ChatGPT" study the kids who used AI to edit drafts after writing on their own did not have the same effect as those who used it for their first draft.

In your post I thought one of the case where the student who asked ChatGPT line by line to explain their professor's lecture would have been a GOOD example of how to use AI. I essentially did this with my TAs in college going to every office hour. I was the type of learner that really wanted to understand the details and needed more help. The beauty of AI is that every student can get their detailed questions answered and explained in a mode that helps them learn. The students who take the agency to find answers with AI are mastering the skill of "learning to learn" anything.

The AI writing the first draft and limiting recall issues are real challenges and personally where I think educators need to experiment with new (or going back to old) methods.

To go back to screen time analogy, as iPad use grew for kids there became a more clear sense of good and bad. The AAP now has standards for it for different age levels. I feel like this is lacking for AI. We haven't aligned as adults on what is "good" or "bad" AI usage so kids don't know either.

I'm looking forward to when we get there as both a parent and supporter of advancing edtech.