AI needs to think before giving feedback

How an evaluation & regeneration loop yields better results for students and teachers

I’ve been working on writing feedback for a long time. In 2017- long before ChatGPT - my team at eSpark developed an AI system to give writing feedback. When I spoke to teachers back then, many told me they were apprehensive about sending AI-generated feedback directly to their students.

Fast forward to today. We have very powerful LLMs, and teachers use them to generate feedback all the time. Yet, they still aren’t quite at the point where most teachers feel that they can trust the outputs completely. Here’s two teachers from the report on use of Claude in education:

Using AI in grading remains a contentious issue among educators. One Northeastern professor shared: “Ethically and practically, I am very wary of using [AI tools] to assess or advise students in any way. Part of that is the accuracy issue. I have tried some experiments where I had an LLM grade papers, and they’re simply not good enough for me.

And this is an issue - because if teachers need to verify everything the LLM does, then it just adds additional busywork:

Most educators seem to agree that grading shouldn’t be anywhere close to fully automated. The ability to evaluate AI-generated content for accuracy is becoming increasingly important. “The challenge is that with the amount of AI generation increasing, it becomes increasingly overwhelming for humans to validate and stay on top,” one professor wrote.

For teachers to get more leverage from AI agents , then the systems need to be more accurate and reliable. But even beyond the issues of accuracy, one-shot responses from ChatGPT or Gemini may also have a number of problems - sometimes the feedback is too wordy, sometimes it is off topic, sometimes the AI can gush with praise for really mediocre work, or the opposite - criticize when a student needs some encouragement.

But there has been quite a bit of research that shows some ways forward.

Teach AI to check its own work

I’ve been reading quite a few papers from the incredible Stanford SCALE GenAI Repository to understand the research landscape. One in particular stood out to me. The paper is called From First Draft to Final Insight: A Multi-Agent Approach for Feedback Generation, published at AIED last summer. Authored by Jie Cao at UPenn and Ken Koedinger of Carnegie Mellon, it looks at one of the most essential elements of an automated educational systems: how do you give quality feedback to students?

In the First Draft paper, they look at one mechanism for improving the feedback: have the AI check its work against a defined rubric before submitting to the students. This simple technique turns out to be surprisingly effective.

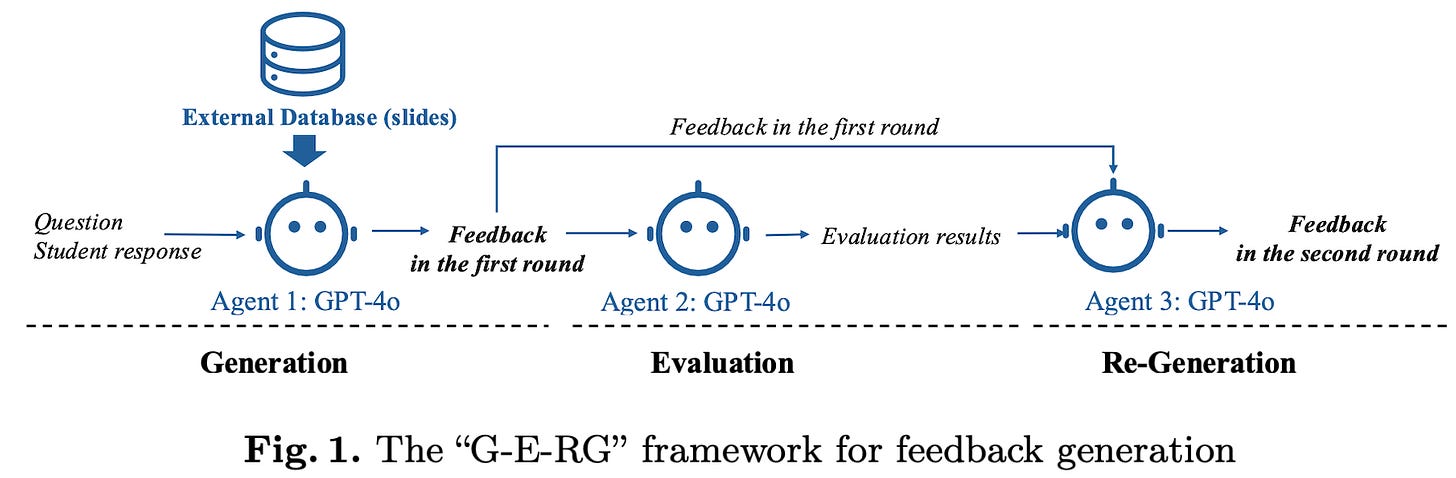

Rather than just generating and delivering the first feedback a model prints out, the authors propose a three-step process called G-E-RG:

Generate. Initial feedback generated using a standard prompt (they tested six different prompts, including some that incorporated source material)

Evaluate. Feed the feedback to a different prompt (maybe a different LLM), and ask to evaluate the first draft against

Re-Generate. Give the model initial feedback, the rubric and evaluation as context, then ask it to try again.

That’s it - the LLM loops once, asks itself to see if it’s good, and then proceeds. The authors tested it on a set of responses from 208 students. They measured the quality of the feedback based on human evaluators. And the outcomes were quite positive.

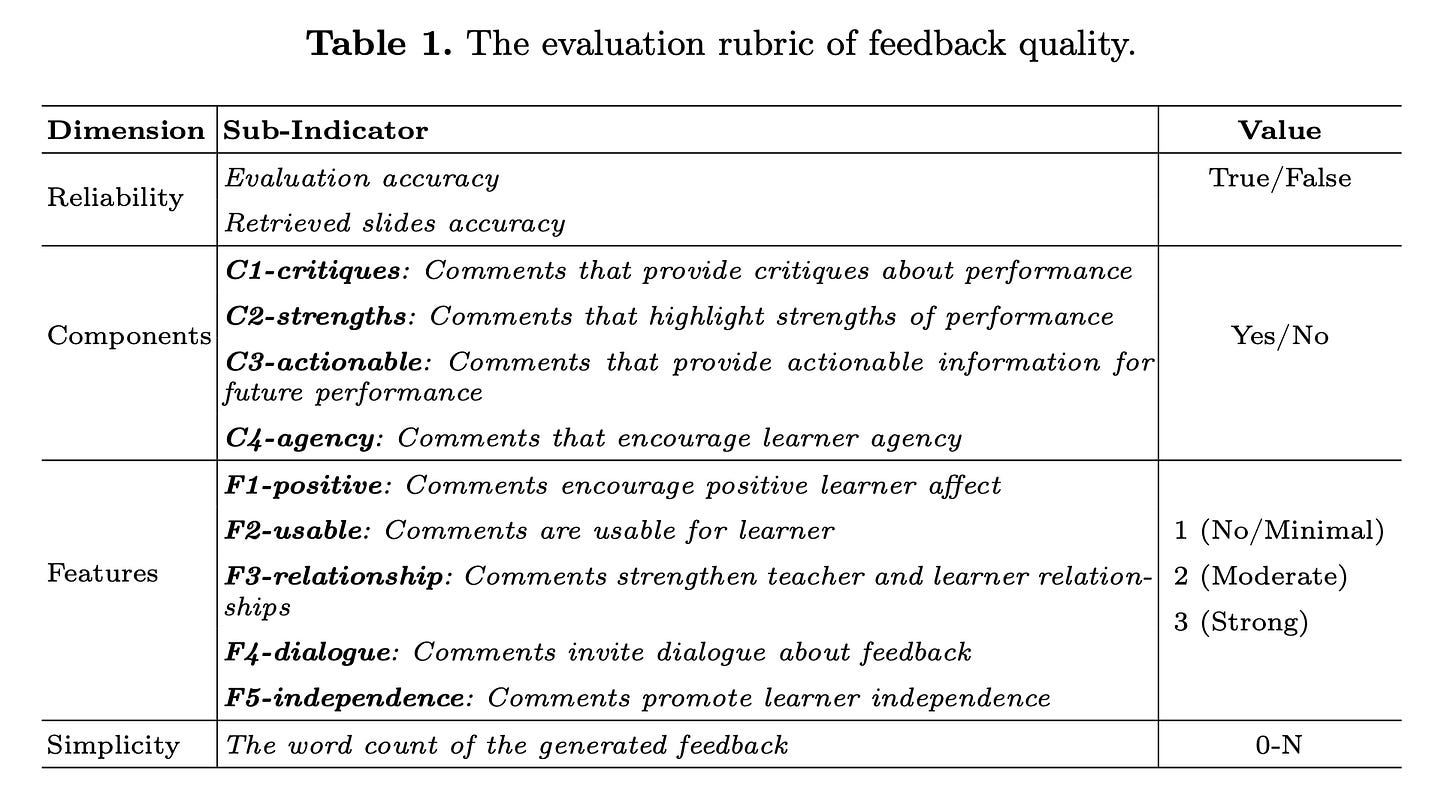

What is good feedback, anyway?

Before we get to the results, it’s worth thinking: what makes good feedback good? In this paper, they formalized some criteria. They want to see first, that it is reliable (does the feedback actually adhere to the truth in the course materials?), then, do the comments provide critiques & strengths, and concrete actionable next steps? They also look for evidence that the feedback would strengthen the learner relationship with the teacher and encourage agency and independence.

The authors found that when an LLM takes a moment to reflect, it did result in better feedback for students. Feedback generated with G-E-RG was on average more accurate, highlighted more strengths of the student response, and suggested more directly actions the students could take. The authors concluded:

Regardless of the quality of the initial feedback, through evaluation and regeneration, it can be transformed into high-quality feedback in the second round, which reduces the instability of LLM-generated content, ensures quality control of feedback, and enhances its applicability in real-world educational settings. This suggests that the “G-E-RG” method is extremely effective in aligning feedback with higher quality.

Do we need a custom frameworks?

But it doesn’t come for free. More computation and thinking means higher cost and latency. And there are simpler ways to just utilize tokens.

Many LLMs, like OpenAI o3 or GPT-5, have a “thinking mode”. This lets them spend tokens before presenting answers to the user. The model decides how to think and what to spend tokens on. In many cases, the thinking mode may decide to run a process similar to the G-E-RG reflection detailed above. And as the models get smarter, such heavy frameworks may become redundant.

But in some cases, a few like custom frameworks for reflection still pay off. A few recent papers illustrate the benefits.

Iterating to success in data science

Data scientists often follow a multi-step, trial and error approach to solve problem. Researchers from China released a preprint in October showing their work on a new DeepAnalyze model which embeds significant inference-time compute. The model uses special tokens to analyze a problem, reflect, and then revise and try again until it believes the problem solved. They found that it did better on a specialized task.

DeepAnalyze consistently outperforms all compared systems across every task. Notably, agent systems built on proprietary LLMs with tool calls exhibit a significant performance drop on open-ended data research tasks compared to more instructive tasks, such as data preparation, analysis, and insight, where explicit steps or goals are provided.

So is data science a specialized loop that may be outside the core training of the major LLM vendors? Seems like for now, yes, and so a specialized inference scaffold shows improvements.

Coding loops

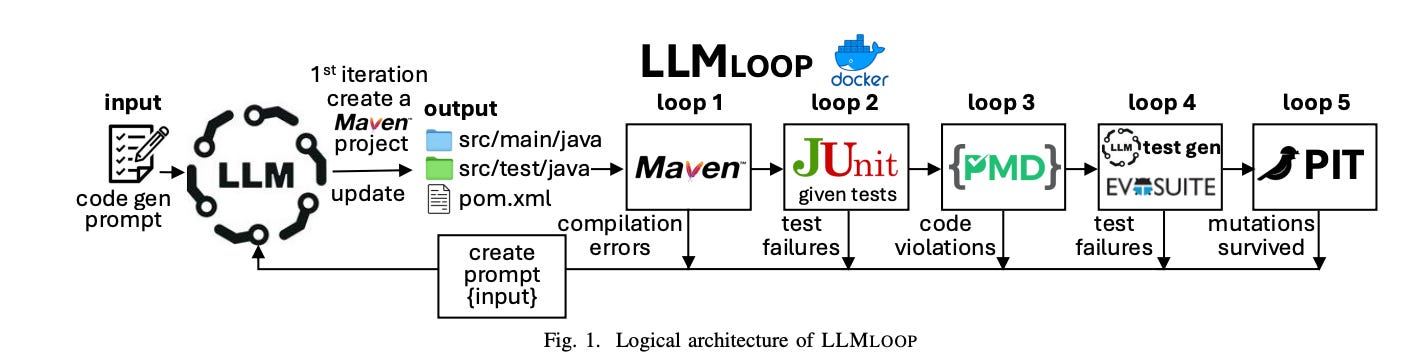

As we see with Claude Code, LLMs can be incredibly effective if they are allowed to operate in a loop - try something, check results, try again, and continue until success is reached. A short paper published in September showcases a new model called LLMLoop. The authors found enormous improvements in specific coding workflows by giving LLM structure and testing out improvements in a loop.

Even without a loop, having structured, systemic steps helped a lot. The baseline initial generation got 71% of the benchmark problems correct. But with structured steps, that jumped to 80%.

But doing multiple loops helps a lot too. When the LLM was able to try 10 times (instead of just one), success jumped to over 90%.

The need for structured loops in education agents

This points to one of the foundational ways to make any AI agent system more reliable: help it reflect and check its work along the way. With coding systems, we see that unit tests, command line tools and build systems can provide checks that are more easily automated.

In education, many steps along the instructional path are squishy and harder to measure and test precisely. It’s easier to tell that a unit test passed than that feedback is excellent, or that a student has understood the material. But as we see here, we can use LLMs to help with the evaluation to maybe overcome that ambiguity and still provide useful tools. They don’t have to be perfect, just good enough to be able to gradually earn trust of teachers and students over time.

This is great! Thanks Luke! I’ve also been looking into flipped feedback frameworks… have the model generate a poor a good and a great draft… then have the student construct feedback for each using a rubric. Put the cognitive effort on the learner to maximize their neural restructuring.

Even though it was a long time ago I remember well all the hours we thought about this problem space. It's almost refreshing to think about how the core problems and perception of good feedback hasn't change. The tech has just caught up where it can be helpful.

One question I have is do teachers feel the draw to customize the feedback models? I have a interview I'm going to post soon to my Substack featuring a PM who works at Github leading their AI code review system and there could some interesting parallels to coding feedback and writing feedback. A lot more investment has likely been done on coding feedback loops and models, and maybe there are some transferable learnings.